Community-Minded Tech

Georgia Tech has a ton of intellectual capital to help solve problems around the world. But what about problems that arise in Tech’s own backyard? Here, we take a look at some of the Tech organizations and people who are helping communities in Atlanta and across Georgia.

By: Kelley Freund

As one of the largest public research universities in the country, Georgia Tech has a ton of intellectual capital to help solve problems around the world. But what about problems that arise in Tech’s own backyard?

When speaking to the local community about the Institute, Chris Burke, who serves as Tech’s executive director of Community Relations, likes to say, “I work for you.”

“We are a public university, and public universities at their core are public good,” he explains.

“With that ethos in mind, we should do what we can to serve the public. And how about we start with our neighbors?”

Those neighbors include some of the most disadvantaged and divested communities in

Atlanta. The city is one of the worst in terms of income inequality, and perhaps these disparities are most evident along the Northside Drive border of campus, where Mercedes-Benz Stadium, the Georgia World Congress Center, and Science Square lie on the east side of the road, and vacant lots and boarded-up buildings can be seen on the west.

In recent years, Burke and his colleagues have been working to further develop Tech as an “anchor institution.” Anchor institutions, such as hospitals or universities, leverage their economic power as well as intellectual resources to improve the long-term welfare of their local communities. By creating more community impact–related programs, such as those that give assistance to local businesses, provide K-12 students greater access to Tech, or offer mentorship, the Institute aims to support those underserved neighborhoods of Atlanta.

And as the next generation’s leaders, Georgia Tech students will play a large role in this.

“We want to make sure our students understand how to be good neighbors and how to be civically minded so they can carry these lessons into their careers,” Burke says.

Here, we take a look at some of the Tech organizations and people who are helping communities in Atlanta and across Georgia.

Project ENGAGES

Taylor Woods, a student at D.M. Therrell High School in Atlanta, says she always had a passion for STEM but was unsure what steps she should take to prepare for a future in the industry. Woods is not alone in this. A lack of racially and ethnically diverse mentors, limited access to advanced science courses, and socioeconomic factors affect the number of minority students who pursue a career in STEM. But a Georgia Tech program is hoping to change that narrative. When Woods heard about the Institute’s Project ENGAGES, she thought it would be the best way to pursue her interests.

Project ENGAGES (Engaging New Generations at Georgia Tech through Engineering & Science) provides high schoolers in underserved communities of Atlanta the opportunity to work for a year in a Tech research lab where they can earn real-world, hands-on experience in STEM fields. The program was launched in 2013 by the late Bob Nerem and Manu Platt, PhD BME 06, who wanted students who live in these communities to see themselves as future researchers at an institute like Georgia Tech.

“We want students to graduate from ENGAGES knowing that they are good enough to be absolutely anything they want to be in the field of science,” says Lakeita Servance, who serves as the program’s project manager. “We want them to know they do look like researchers.”

ENGAGES works with seven schools in Atlanta: Coretta Scott King Young Women’s Leadership Academy, B.E.S.T. Academy, South Atlanta High School, Benjamin E. Mays High School, D.M. Therrell High School, Booker T. Washington High School, and Charles R. Drew Charter School. Interested juniors and seniors go through an application and interview process before beginning the program in the summer. During their time with ENGAGES, each student works on a unique research project in areas ranging from robotics and coding to biotechnology and aerospace engineering. Graduate students, who are also selected through an application process, serve as mentors and oversee the projects. Students also gain additional exposure to new research and medical technology through industry visits. Businesses such as Axion Biosystems, C.R. Bard, and Dendreon have provided tours to participants and educated them on their industry and employment opportunities.

Scholars participate in ENGAGES for an entire year, and Servance says the length of the program is one of the things that sets it apart.

“With an eight-week summer program, there’s just not enough time for these students to conduct research, have exposure to different opportunities, such as attending conferences, or receive mentoring,” she says. “A year-long program allows them to experience all of that.”

Another unique trait of the program is that students are paid for their research work. Servance says many of the students in the program come from socioeconomically challenged households, and those students often have jobs that help support their families. “We didn’t want students to have to choose between a job or pursuing their goals academically,” she says.

As an ENGAGES scholar, Woods worked on research to identify Cathepsin K, a potent human protease (meaning it breaks down proteins at a fast rate), as the main cause of elastin and collagen degradation in sickle cell–diseased arteries. Woods and other ENGAGES participants were also able to attend the Emerging Researchers National Conference in STEM, held in Washington, D.C. Servance says these conferences provide students with the opportunity to see more diversity in STEM fields, which they might not be able to witness in their local communities.

“I enjoyed getting the chance to speak with many different people from different backgrounds,” Woods says. “I also enjoyed the fact that no one treated me like a child. I was looked at as if I was an adult and had a say. These experiences continue to push me forward.”

Woods says she is considering attending Tech because of the connections she has made and because of her familiarity with the campus and lab spaces. She’s unsure of what field she wants to go into but thinks biology will allow her to keep her options open.

Since its launch, over 150 students have participated in ENGAGES. This coming year, thanks to support from the program’s partners like The Coca-Cola Foundation, the program is able to offer double the number of spots. Servance says that’s a huge deal for a program that changes the trajectory for so many of its participants, some of whom go on to be first-generation college graduates. (Some are also first-generation high school graduates.)

Earlier this year, Georgia Tech received a grant from Johnson & Johnson that will provide even more opportunities to high schoolers interested in STEM. As part of the grant, ENGAGES will serve as the coordinating site entity for Johnson & Johnson’s Bridge to Employment (BTE) program, which will mentor and support 35 to 50 high school students who are too young to apply for ENGAGES. Servance says her hope is that BTE participants will become excited about STEM and want to apply to be an ENGAGES scholar when they become eligible.

“I think it’s important for Georgia Tech to show we are invested in pouring back into our local communities,” Servance says. “We want to retain the talent that is in our own backyard. We want these local students to see Georgia Tech as a real option. And the way to do that is to open our doors and welcome them early so that we can break down those barriers, those myths, those fears they have of not belonging here.”

Flourishing Communities Collaborative

Associate Professor Julie Ju-Youn Kim (right) leads FC2, which offers design solutions to disadvantaged communities in and around Atlanta.

In the fall of 2022, Spencer McMains and a group of fellow students in Georgia Tech’s School of Architecture came up with an interesting solution to create an affordable community space in the English Avenue neighborhood of Atlanta: use shipping containers.

This unique design project was created by the school’s Flourishing Communities

Collaborative (FC2), an academic lab founded by Associate Professor Julie Ju-Youn Kim in 2017. Through the collaborative, students work in partnership with faculty and professionals to offer design solutions to neighborhoods that are traditionally disadvantaged. People in these communities often lack access to affordable housing, jobs, educational opportunities, and other quality of life factors. But according to Kim, architecture is a great way to address these critical issues.

“An act of design is an act of optimism and hopefulness,” Kim says. “How can we change this existing condition to a more desired one? Through architecture, we can strengthen our communities and promote equity, diversity, and inclusion. All of that is wrapped up in FC2.”

In the case of the community space in English Avenue, McMains and other students set out to help stabilize a historically vibrant but shrinking neighborhood by designing a space consisting of shipping containers that could house coffee and food vendors and an art gallery, and provide a place for people to relax. The project is currently in the hands of neighborhood leaders to raise funds.

McMains says the experience taught him that architecture is not just about making pretty buildings, but having a positive impact on the community.

“The strength of a city lies in addressing the needs of its most vulnerable members,” he says. “By actively making a difference in the lives of those who often go unnoticed, we have the opportunity to produce a more sustainable and inclusive environment that benefits every resident, regardless of their circumstances.”

As with the shipping container project, FC2 has focused much of its work on the Westside neighborhood in recent years. Ranjitha Jayasimharao, another FC2 participant, believes it’s important for institutions like Georgia Tech to help these disadvantaged communities.

“A university is a place where there is immense opportunity for research and innovation,” she says. “I think it’s our responsibility to make an impact on immediate challenges through action and outreach. I strongly believe that through collaboration and leadership, we can create meaningful change.”

In the summer of 2022, Jayasimharao served as FC2’s building performance analyst to help the collaborative create an affordable housing prototype that would use less energy than a conventional home. But through the project, students realized some homeowners weren’t always aware of the ways they could manage their own energy consumption. For example, some didn’t know the difference between LED and incandescent bulbs.

Jayasimharao says that the group decided that an educational approach would play a bigger role in addressing environmental inequities within the existing homes. So the group created a website, Smart Old Home, to provide the community with simple and useful information on weatherization that would reduce utility burdens.

In the coming year, FC2 participants will focus their efforts on a Sustainable Mobile Learning Lab that will provide hands-on demonstrations and programming throughout the Westside community. Kim says the lab will be deployed in spring 2024, and imagines it could also be used as a place to receive free flu shots, as a popup farmer’s market, or a place where the community can come and learn how to grow their own tomatoes.

Although the mobile lab is a simple structure, Kim says the mission behind it is important.

“I hope students see a range of ways that they can engage in this discipline we call architecture,” she says. “I hope they see how they can contribute to building more equitable environments and empower communities through design, and then implement similar kinds of strategies in their own practices.”

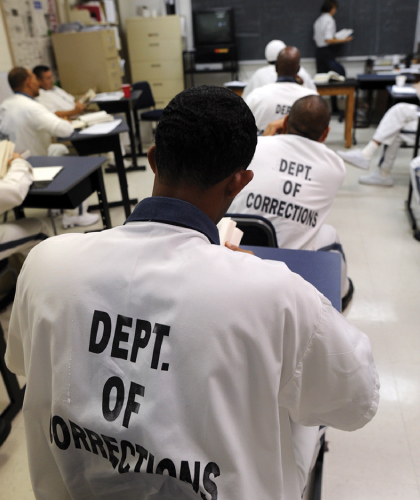

Common Good Atlanta

Former Georgia Tech Brittain Fellow Sarah Higinbotham spent her college career studying literature, so by the time she entered Georgia State University to earn her PhD, she recognized the humanities had the power to transform people. She decided to focus her doctoral work on that concept. Higinbotham had once heard about programs that provided incarcerated people with access to higher education opportunities by connecting local college professors with prison classrooms, but discovered there was no such thing in Georgia. So she set out to see if she could teach on her own, without the backing of an official program.

After writing to 17 wardens, she began teaching at Phillips State Prison in 2008. One semester turned into two. Two semesters turned into two years. Then, along with grad school friend Bill Taft, Higinbotham officially turned their education work into a nonprofit: Common Good Atlanta.

Since their inaugural class in Phillips State Prison, Common Good Atlanta has expanded into several other prison facilities, including Metro Reentry, Whitworth Women’s, and Burruss Correctional. Over 60 professors from seven Georgia universities have taught thousands of hours of college-level courses, including Shakespeare, writing, U.S. history, art history, philosophy, neuroscience, and algebra.

“Historically, there have been gatekeepers around some of these subjects,” Higinbotham says. “In our culture we’ve told some people they are Shakespeare material and others that they are not. These students are coming from our most vulnerable communities, in terms of things like education, healthcare, and housing, and they’ve been told by our system that they are not college material. But then they read Plato and Shakespeare, and they think, ‘Wait, I totally get this.’ They are gifted and deeply intellectual individuals.”

Eric Schumacher, a professor in Georgia Tech’s School of Psychology, first heard about Higinbotham’s work on a radio program over 10 years ago, before there was an official Common Good Atlanta. He had been doing volunteer work with Habitat for Humanity, but jokes that he wasn’t particularly handy and thought it would be a good idea to use the skills he actually had. So he reached out to the radio station, which put him in touch with Higinbotham. Since then, he’s taught courses in prison facilities surrounding topics of psychology, neuroscience, and stress disorders.

Schumacher says teaching in a prison classroom is a little different than teaching at a college.

“In this environment, there isn’t really that ‘sage on the stage’ dynamic, where I’m up there lecturing,” he says. “These students are very interested in the topic, and when I come to the classroom, they are ready with their questions and not inhibited about engaging in discussion. Professors don’t always get that in our typical college classes. It’s very rewarding, and also it’s a lot of fun when your students are really interested in the coursework.”

Georgia Tech’s connections with Common Good Atlanta run deep. Former Academic Director Jonathan Shelley is a former Brittain Fellow, as is the organization’s current Academic Director, Eric Lewis. Not only is Ruth Yow a former Brittain Fellow, but she currently works with Tech’s Center for Serve-Learn-Sustain and has also taught in the prison facilities. Sai Nakirikanti, Neur 20, is now a second-year medical student at Emory University and the founder of Emory Medical Students for Justice. Through that organization he has inspired medical students to go into prisons through Common Good Atlanta and educate incarcerated people about health.

Current Georgia Tech students also have opportunities to be part of Common Good Atlanta. In 2016, in celebration of Shakespeare’s birthday, a group of students from the Institute visited Phillips State Prison for a combined discussion with incarcerated students on Much Ado About Nothing.

“We often rely on flattened narratives about who people are and what they’re capable of,” says Higinbotham. “So what a paradigm shift it was for these students to go from a media perception of people in prison to actually sitting in a room with them and discussing Shakespeare. The more we have proximity to people unlike ourselves, the more we begin to understand that our differences are the most valuable thing we have.”